The Renewable Fuel Standard is a program that falls under the administration of the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). It was started with the Energy Policy Act of 2005 and expanded under the Energy Independence (aka RFS I)and Security Act of 2007 (aka RFS II). The program is a national policy covering the lower 48 states and Hawaii, with the option for Alaska and US Territories to opt-in.

The program’s goal is to put renewable fuels in place of fossil fuels, with compliance separated into 4 categories of renewable fuels in the program that qualify:

- Biomass-based Diesel (minimum 50% lifecycle GHG reduction, generating D4 RINs)

- Cellulosic Biofuel (minimum 60% lifecycle GHG reduction, generating D3 or D7 RINs)

- Advanced Biofuel (minimum 50% lifecycle GHG reduction, generating D5 RINs)

- Renewable Fuel (minimum 20% lifecycle GHG reduction, generating D6 RINs)

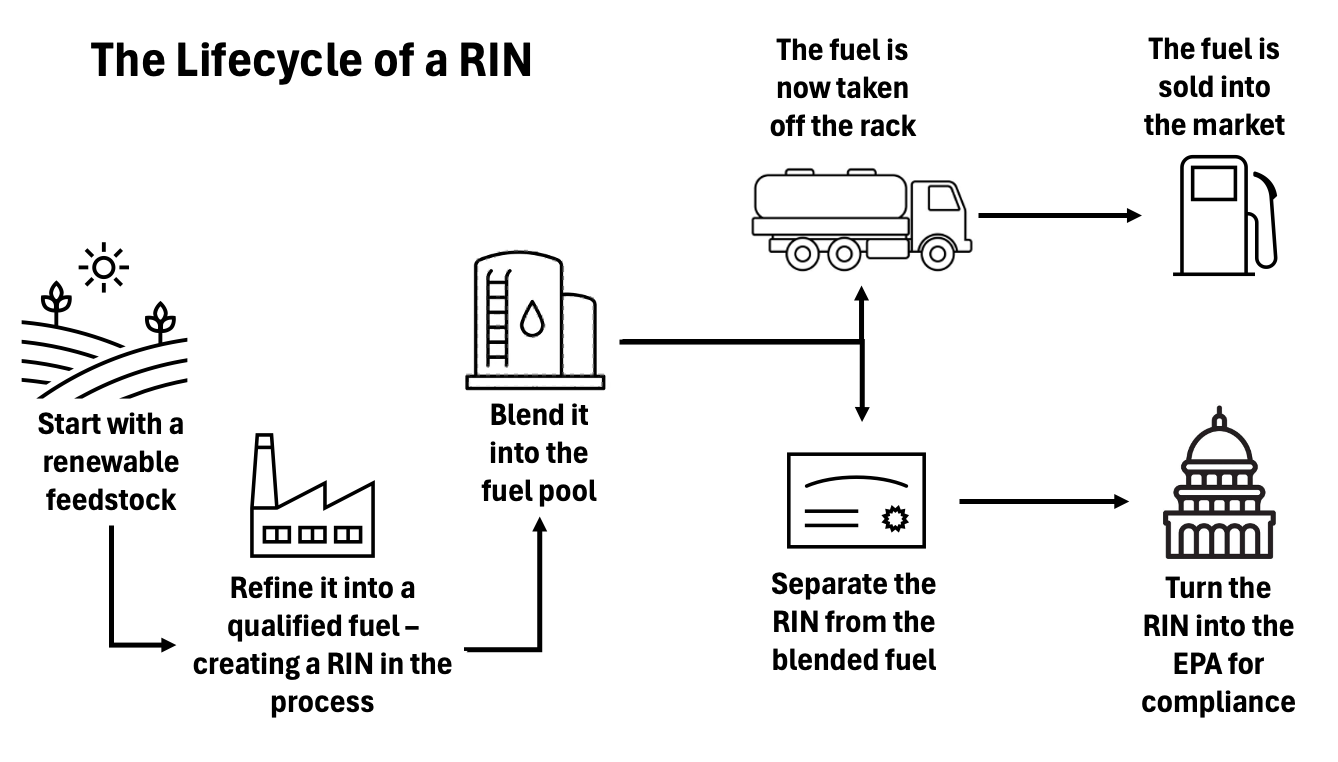

Each year, refiners are mandated by the EPA to blend a certain amount of the aforementioned fuels into their products. Each fuel is defined by qualified inputs (“qualifying renewable biomass”, cellulose, etc) and lifecycle GHG reduction based on a 2005 baseline (noted in parentheses after each fuel above). To demonstrate compliance with the program, refiners turn in Renewable Identification Numbers (RINs) to the EPA every April for the prior year’s obligations

Demand

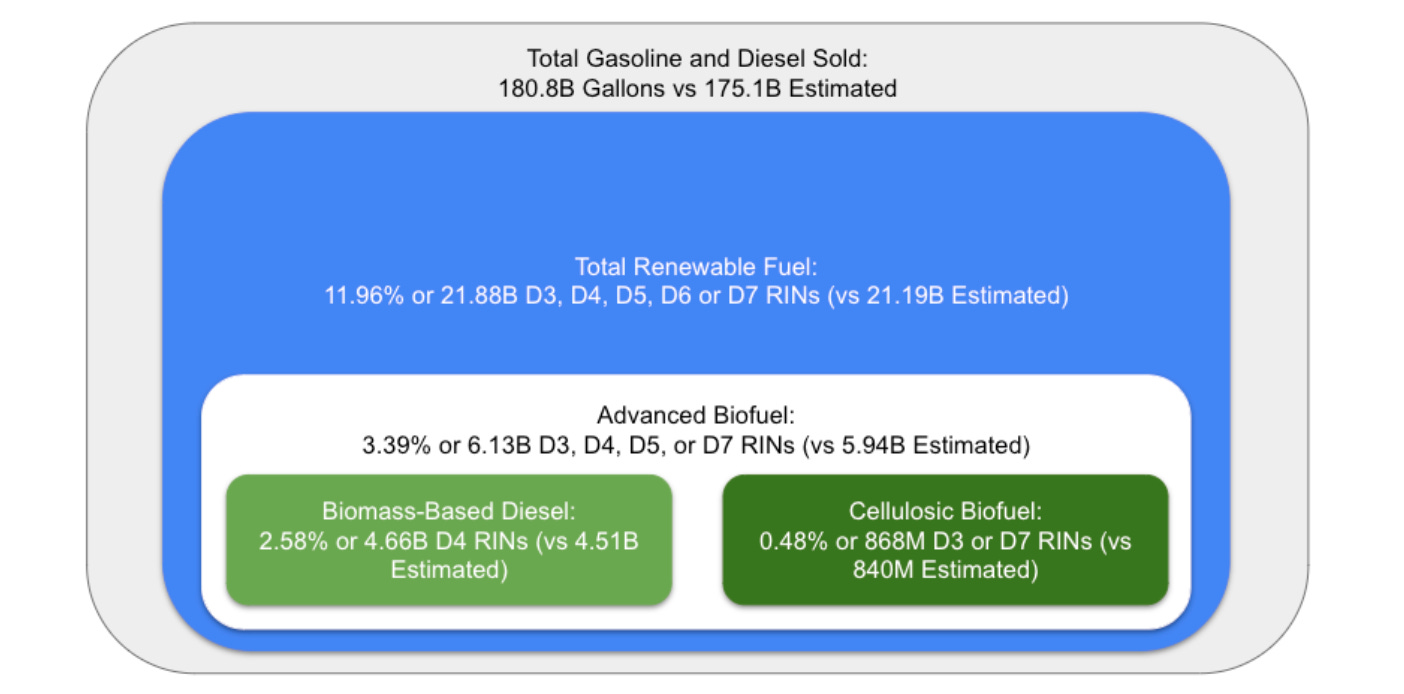

The EPA has the authority to establish the renewable volume targets, which is known as the Renewable Volume Obligation (RVO). When the EPA (often belatedly) publishes these targets, it is done with mandates for different fuel categories. This is particularly important because depending on the D code corresponding to the fuel category, some gallons may earn more than 1 RIN (for example, a gallon of biodiesel earns 1.4 RINs). In the illustration below, we can see that biomass based diesel (D4 RINs) and cellulosic based diesel (D3 or D7) are part of the entire advanced biofuel mandate, which in turn is part of the total renewable fuels mandate. This means, for example, excess D4 RINs can be used to satisfy D6 needs. However the process does not move backwards, for example, excess D6 RINs cannot be used to satisfy the mandate for biomass based diesel (D4 RINs). While the headline target volumes are given as an estimated target, the actual final obligation is a percentage of total gasoline and diesel fuel sold by compliance entities (which means, if the estimated fuel sold diverges significantly from actual fuel sold, obligations will be quite different from the published volumetric target).

The final obligation volumes are not public until the EPA reports it in May of the following year after compliance is finished in April. To make this more clear we have the following image using final 2023 requirements against the estimated targets:

Demand, as mentioned, is based on the percentage of gasoline and diesel sold by obligated parties dictated by the EPA’s RVO. In 2023, the divergence of over 5 billion gallons in the estimated fuel sold and actual fuel sold was significant and will be something to watch as the EPA assumed demand would fall further in 2024 and 2025 (as of this posting we are still waiting on the 2026 RVO).

One kink in the demand equation is a small refinery exemption, or SRE, which allows refiners who process less than 75,000 barrels per day of crude oil to apply for an exemption from the RFS. If granted, it removes their fuel produced from the final obligation calculation as well as the refinery from any compliance obligation. The SRE has been a hot political issue and the EPA’s attitude towards granting them shifts with each new administration, frequently ending in lawsuits no matter which way it goes.

In addition to SREs, a refiner may also elect to defer part of their obligation for one year, however they cannot defer an obligation for the same category of fuel 2 years in a row. The deferred volume from the prior year is added to the final obligation for the current year RVO. In 2023, these deferrals reached an all time high of over 2 billion total RINs deferred to 2024.

Supply

RINs are created with the renewable fuels when they are produced or imported. The most common fuels are corn ethanol, sugarcane ethanol (mostly imported), renewable diesel, and biodiesel. The value of a RIN is critical to the production margin for renewable diesel and biodiesel, although (interestingly) it is not as critical in the production of corn ethanol. As for imported volumes of renewable diesel, biodiesel, and sugarcane ethanol RIN values (along with other credits like California’s LCFS) are a major factor in opening an arbitrage opportunity.

RINs have a lifespan of up to 2 compliance years, for example a 2023 vintage RIN can be used for 2023 or 2024 obligations. There are restrictions though, as only up to 20% of the current obligation can be met with prior vintage year RINs. This carry over from year to year is known as the “RIN Bank” and it is a key figure that market participants watch for gauging how tight the market may be.

As discussed in short earlier, RINs also have a one-way fungibility from more advanced biofuels to fill mandates for less advanced fuels. In more simple terms, a biomass-based diesel D4 RIN can be used to satisfy a compliance requirement for a D4, D5 or D6 RIN. The D3/D7 and D4 are the only 2 that must be satisfied by their own supply, unless a waiver is granted and paid in the D3 market, then the waiver is typically turned in with a D5 RIN for D3 compliance. The recent growth in supply of D4 RINs has been able to cover up shortfalls in D5 RIN generation as well as the inability to blend enough ethanol (D6 RINs) into the gasoline pool to cover the gap between advanced and total renewable fuel mandates.

RIN Market Dynamics

Without delving too deep into the history of RINs, the program was initially set up with a clear target of initially using corn ethanol to satisfy most of the mandate before transitioning more into the advanced fuels. The final technological stop being cellulosic fuels, which were were meant to take over the lion’s share of the market. This never materialized, both because certain technologies never became economically feasible, (cellulosic ethanol remains in short commercial supply) as well as the reality of modern politics (biodiesel and corn ethanol are massive markets for the American farmers).

Early in the program, D6 RINs were abundant and cheap (trading under $0.05/RIN) while D4 prices moved with the cost of blending biodiesel into the diesel pool. D5 RINs were tied to the price of a D4 (usually a small discount). D3 RINs, on the other hand, were almost entirely satisfied via waivers. Around 2013, the market hit what was known as “the blend wall,”, where the standard cap of 10% ethanol blending into gasoline meant there was no way to blend enough fuel to cover the growing mandate and prices jumped well over $1.00 for D6 RINs. This period was known as “RINsanity” (the market has a sense of humor at least) which led to major showdowns between the Farm Lobby and the Refiner Lobby.

To simplify the history, this situation has more or less been abated by the rise of a new process to make a biomass-based diesel known as renewable diesel - a “drop in fuel” (meaning it meets all the specifications of conventional diesel and can be used as an entire replacement for diesel vs. 10-15% blending for ethanol or 5-20% blending for biodiesel). Combined with the value from concurrent programs like California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard, the margins for producing renewable diesel were so large that the industry climbed from a few hundred million gallons in 2016 to around 5 billion gallons in 2025.

This has shifted the focus of the market from the blend wall to watching biodiesel and renewable diesel margins. Since the beginning of the RFS the US gave blender’s credits for using these fuels (yes, a credit for using a fuel they are mandated to use), but over a decade ago the ethanol market lost their credit (with little fanfare) while the biodiesel industry has fought tooth and nail to keep their $1/gallon blender’s credit (or BTC).

Under the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, congress extended the BTC, one last time, to December 31, 2024. From January 1, 2025 onwards, it would be replaced by a new credit only available to producers based in the US and it would be tied to how much of a GHG reduction the fuel had under a new GREET model. This switch has been anything but smooth and clear to the market, leaving RIN prices volatile over the end of 2024 and early 2025. The final major driver of price is the relationship of feedstock price against the cost of a gallon of conventional diesel. This is typically seen through a proxy of the relationship of soybean oil price to conventional diesel price (known as the BOHO spread) and has the most price impact day to day.

Participants in RIN Markets

The participants in the over-the-counter market for RINs include fuel refiners and wholesalers who are covered for compliance in the USA, the biofuel producers or importers of biofuels, as well as a slew of other trading entities in the market such as commodity trading houses and a few funds. The bar to entry in the over-the-counter market is signing up for the EPA Moderated Transaction System (EMTS), so many participants have entered the market in the past decade. In addition to the OTC markets, there is a reasonably liquid futures market for D4 and D6 RINs and a less liquid contract for the D3 RINs.